|

HOME - Rosa Maria Ponte paintings: An explosion of colour

by Prof. Carmelo Fucarino

English translation by Vanvakys edited by Prof. Judy Rozner

Art is neither male nor female

Reflecting on Western Art from its first manifestation in Greek and later Roman societies, art was not Reflecting on Western Art from its first manifestation in Greek and later Roman societies, art was not

only exclusively an activity performed by males but was also directed as commissions towards male collectors. Rare, and for various reasons, were there women painters. It is still a common belief that art is the domain of men. Does it still deny women? What about in conducting an orchestra.

Let us not consider female artists presence in ancient Greece and Rome such as the celebrated

Timarete and Irene, or Corinzia who had first traced her departing lover’s profile on a wall, or Marzia, “the youngest daughter of M. Verrone who with brush or with an ivory pen depicted mostly images of women and a large painting in Naples of an elderly woman and herself reflected in a mirror.” (Plinio the Elder n. h. xxxv, 147). Let us ignore the many women ensconced in the silent cloisters or in the austere halls of Medieval palaces, who were the feminist ante litteram, able to fight for women’s self determination but forever remain isolated from the passages of history. In the whole tradition of the history of art, women were only sporadically acknowledged as painters, or allowed to work as artists, in what was considered heavy duty male occupation, sculpture.

The true revolution started with Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652), The first modern woman to execute a self-portrait of her reflection in a mirror, a painter who is more famous and often noted as a model feminist in a masculine environment arising from the tragedy of her rape; for her courage to publicly denounce it and as an innovative artist. She had proved herself twice: as a woman as well as in her original interpretation of the Caravaggesque style, in the realistic depiction of female heroines in the Penitent Magdalene and in the cruel and gruesome depiction of Judith Beheading Holofernes.

But, the role model and prototype of woman-painter was Sofonisba Anguissola, (c. 1532-1625) the first in a long series of women who were dedicated mainly to portraiture. Many women-artist followed this line until we reach the innovations of Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), a model and a friend of Edouard Manet, who had instructed her in the new Impressionist style of Plein-air paintings. We now reach Tamara De Lempicka and Frida Khalo, at the beginning of 19th Century when at long last a slow progress was made during the century in reaching equal rights in the arts.

In modern society women’s creativity no longer surprises anyone. It had also been affirmed in other artistic activities, moreover, there is now an ascendance in feminine presence in art shows, in performances and art critique, as well as in the management of museums and art departments; a rapid and overwhelming process. Nowadays, rather than resistance, the debate, that had started as a negative in the feminist movement, as women’s revenge and women’s power, is it still possible to speak of “feminine art” or “women’s art”? Until this barrier is breached the question of “feminine” will continue to permeate the arts and remain unsolved.

Because art does not have definitions of genders and sex, neither male nor female, not male painter or female painter, art is by all and for all, art is universal. No one ever thinks of interpreting poetry or a simple expression of a song as feminine or masculine art.

Moreover it is possible to single out in reality the expression and the interpretation of a point of view from other parts of the world in its particular style and category to which it belongs, as diverse people read reality from different points of view. Blues music is an expression of a painful reality of a particular social class, that was derives from slaves seeking redemption. For that reason a painting by a woman has an expression of her own particular view of the world, her own specific sensibility, but this does not make it inferior or superior, it is simply a different approach; perhaps moulded by her ancestral or secular habits.

Rosa Maria Ponte and her pictorial category

Rosa Maria Ponte paintings, for this reason, are her way of reading reality that differs from any other painters’ reality, men or women. It is an interpretation that is rooted in her cultural upbringing, in her reading and in her artistic knowledge, but also in her sensibility formed by occurrences and experience. Therefore her painting does not have ancestry or a master; it does not follow a school or a plan. It is her art. It is only possible to attempt to give her framed work a classification of its realisation as a work of art. Rosa Maria Ponte paintings, for this reason, are her way of reading reality that differs from any other painters’ reality, men or women. It is an interpretation that is rooted in her cultural upbringing, in her reading and in her artistic knowledge, but also in her sensibility formed by occurrences and experience. Therefore her painting does not have ancestry or a master; it does not follow a school or a plan. It is her art. It is only possible to attempt to give her framed work a classification of its realisation as a work of art.

Meanwhile, the only means of technical expression are oil on canvas, an established technique, the most perfect and long lasting, different from pastels and watercolours, or pencil drawings that were born from the temporary note and reached its full realization in which it became exhausted.

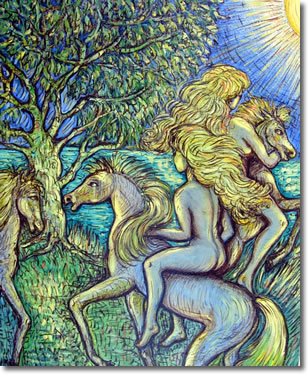

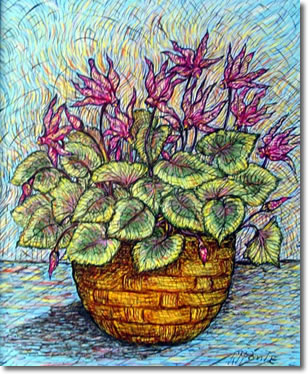

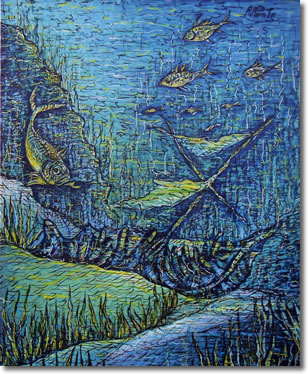

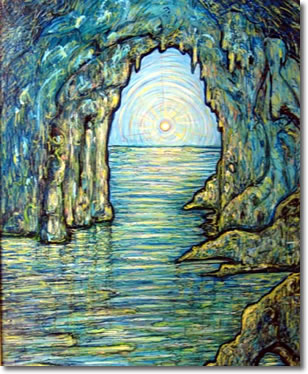

The other fundamental element of her art is in the use of the brush, with repetitive development of points that step by step are expanding in their construction of the image, and her use of very small brushed is a proof of her immense patience. One would never find any large strokes of a large brush or a spatula smear. Her creation develops gradually, point by point, through a careful and meticulous formation of the material. Sometimes an imaginative figure or scenery finds support with the application of gold or an object that had by chance fallen on the wet paint.

Then there is her process of colouring, with her inimitable and unique mixtures of colours with the aim of obtaining the exact right shading, unique within the infinite scale in the tonal shades of the rainbow.

Pliny the Elder author of “The Natural History” had already describes in more than 22 chapter the variety and elaboration of colours, all exclusively natural, of different types that had exotic names of Asian provenance. He records primitive paintings that were made with a single colour of a mineral. He wrote that “to discover different types of colours is the prime motive in the undertaking of a work of art.” However the same art is differentiated with the discovery of light and shade that mutually provokes the difference in colour. Then eventually the splendour is added, which is different from the light. That which is between light and shade is called chiaroscuro (tonon), indeed a fusion of colours and shading that he named Harmogen, a mastery of colour combination. (Pliny the Elder, n. h. 29)

In the large variety of the pallet, green is blinded in the hope of yellows, whites, and reds are driven to burning fire, all dazzling and dominated by a blue, the colour which is shrouded in mystery that wraps and fills space, anxious for liberty and thirsty in the search of infinity. Baudelaire who had tinted some of his lyrics with the colour of azure gives way to blue. There is an explosion of hues that in the ardour of their manifestation they subdue reality and surpass it to realise a concept, a real idea. In the end the inscribed subject becomes a prescribed category. In the landscape of famous and exotic urban cities, it dazzles men, women and monuments, from Monaco to Rangoon and on to Morocco, in a long list of countries that had left their mark on its soul. Much as the natural foreshortening of a creek or a lake where the blue of the water is central and sometimes used as the background for the human figure.

Then there is what we call still life with its wide variety of floral images scattered on an enchanted background; object of everyday life seen again and coloured by the soul. The female form, alone and unique, a true extension of her inner self, in different poses and attitudes as revelation of dreams; it is not in vain that we go from the gyrating Flamenco to the tales of Scheherazade.

Reflections and thoughts about Rosa Ponte’s Catalogue

These reflections are not a diagram of variations that addresses themes. It is solely reflective notes. The entire vocabulary of subjects trough colours are offered with a careful viewing of the catalogue, painting by painting; an inner pleasure that can only be attained by a long observation; fronting the image thay explodes form its frame that a simple verbal exercise can describe.

Inspiration of Blue in romantic and symbolist poetry

First and above all it is Baudelaire with his numerous recalls to azure. Then there are five champions that magnify this celestial colour.

Stephan Mallarme’ raises it to an absolute theme, a symbol of immaculate purity on “L’Azul” (The Azure) lyric poetry composed between. 1863 and 1864: First and above all it is Baudelaire with his numerous recalls to azure. Then there are five champions that magnify this celestial colour.

Stephan Mallarme’ raises it to an absolute theme, a symbol of immaculate purity on “L’Azul” (The Azure) lyric poetry composed between. 1863 and 1864:

[…] En vain! l'Azur triomphe, et je l'entends qui chante

Dans les cloches. Mon âme, il se fait voix pour plus

Nous faire peur avec sa victoire méchante,

Et du métal vivant sort en bleus angelus!

Il roule par la brume, ancien et traverse

Ta native agonie ainsi qu'un glaive sûr;

Où fuir dans la révolte inutile et perverse?

Je suis hanté. L'Azur! l'Azur! l'Azur! l'Azur!

So as he commented: “The sky is dead!” He then reafirms in admirable certainty and implore the Substance. Here it is the joy of Impotence. Tired of this disease eroding me I want to taste the common happiness of the crowd and wait for an obscure death… I say “want”. But my enemy is a ghost and the dead sky is back I hear it singing in azure blue bells.

Rafael Alberti, a cheerful poet, writes: “My childhood was full of bright blue colors in Puerto De Santa Maria…. and I reiterated it, almost till losing my voice, in the songs of my first books. I opened my eyes among blue uniforms, to the navy azure blouses, the skies, the river, the bay, the islands and the breeze”.

To Juan Ramon Jimenez the colour blue is one of a recurring chromatic theme representing his poetic ideal and its spirituality:

In Dios esta’ azul (in Baladas de Primavera 1910).

The search for God; the truth and the exact name of things is realized through verses from Animal de fondo (1949):

“Coscienza oggi di vasto azzurro,

coscienza desiderata e desiderante,

dio oggi azzurro, azzurro, azzurro e più azzurro,

come il dio della mia azzurra Moguer,

un giorno”

An elegy by Federico Garcia Lorca (April 1919, from the book Lobro de poemas (1921):

El mar es

el Lucifer del azul.

El cielo caído

por querer ser la luz.

¡Pobre mar condenado

a eterno movimiento,

habiendo antes estado

quieto en el firmamento!

Pero de tu amargura Pero de tu amargura

te redimió el amor.

Pariste a Venus pura,

y quedose tu hondura

virgen y sin dolor.

Tus tristezas son bellas,

mar de espasmos gloriosos.

Mas hoy en vez de estrellas

tienes pulpos verdosos.

Aguanta tu sufrir,

formidable Satán.

Cristo anduvo por ti,

mas también lo hizo Pan.

La estrella Venus es

la armonía del mundo.

¡Calle el Eclesiastés!

Venus es lo profundo

del alma...

...Y el hombre miserable

es un ángel caído.

La tierra es el probable

Paraíso Perdido.

And finaly Eugenio Montale the modern poetry illuminated by azure blue:

[…]un uomo

che là passasse ritto s'un muletto

nell'azzurro lavato era stampato

per sempre

e nel ricordo (Fine dell’infanzia, vv. 32-35,)

Meglio se le gazzarre degli uccelli

si spengono inghiottite dall'azzurro (in I Limoni, vv. 11-12). |

|

|

|